WATER HISTORY WEDNESDAY | EDITION 09

The London Sewers was an extremely important addition to London’s underground, driven to creation, not by the filth lining the streets or the waterborne diseases sweeping through the population, but by London’s hot summer of 1858.

It’s true that leading up to the 19th Century, London didn’t have an effective manner of dispersing waste and had garnered a poor health reputation as a result. Early on, there were around 200,000 cesspools in homes and businesses in the city. These cesspools were meant to be emptied by nightsoil men and carted off to be sold as fertilizer, however, the system was unreliable and many of the cesspools remained stagnant. So the people took to emptying them onto the streets. Free to wash away with the rain, it would travel downhill until it made it into the Thames River.

In 1848, the Metropolitan Sewers Act was passed to help with the issue, allowing sewage to be taken from properties and dumped into the Thames. With the rise in flush toilets, wealthy families had their waste dumped directly into the Thames River. The problem, however, was that the Thames was still largely used for washing and even drinking at the time.

Unsurprisingly, this had a disastrous effect on public health. Records suggest that only half of London’s infants lived to their fifth birthday with cholera and other diseases becoming more common. Since the first recorded case in England in 1831, there were two major outbreaks of cholera reported, in 1849 and again in 1854.

Yet the English didn’t know why. They still believed that these diseases were a result of ‘miasmas’ or bad air. It was a philosophy that the Romans had believed but had dealt with much better, having created their sewers to direct waste away from the city, thus eradicating the smell and unbeknownst to them, minimising waterborne diseases.

It wasn’t until Dr John Snow that the true cause was found. He had attended the patients of the cholera outbreaks in 1849 without contracting the disease himself, and by the time of the second outbreak in 1854, he was able to track the source of the disease to a popular water pump in Broad Street. He was able to deduce that the outbreaks were not transmitted through the air but through the water. He was unaware of it at the time, but the sewer had been leaking into the Broad Street well.

Despite some 10,738 lives lost throughout 1853-54, unfortunately, that discovery didn’t spark change. Although the Metropolitan Board of Works had wanted to bring updates to London’s sewer systems, they weren’t able to achieve the funds required to make any developments.

That was, until the time of the ‘Great Stink’.

The summer of 1858 marked a great change for the city of London. The weather had taken a turn, with the city experiencing a period of extremely hot temperatures for the region, consistently resting above 30 degrees Celsius, and the extreme days reaching over 35 degrees.

With the heat, came the smell. The Thames River had been so contaminated, that the summer heatwave caused horrendous smells to fill the streets surrounding its embankment.

It was not just human waste contaminating the river either, the Thames had been treated as a dumping ground for all sorts of waste including waste from livestock, homes, businesses, hospitals, schools and prisons. Chemical and organic waste from soap works, tanneries, factories, slaughterhouses, and mills. Anything in the streets flowed downhill into the river, and it all combined to create a great toxic mix.

During the of the ‘Great Stink’ the waterways of London were considered a public health risk. Records of the time even suggest that the smell of the river was so noxious, that people who got too close to the Thames suffered from apoplectic fits, fainting and vomiting.

So what was done about it?

Thanks to the ‘Great Stink’, more notice was taken of the conditions of the river. The House of Parliament was so distraught by the smell that they had the new blinds being installed in the building soaked in chloride of lime so that the people could tolerate being inside.

This similar technique was used on the river itself, and they initiated throwing lime into the Thames in an attempt to deodorise it. In early July 1858, approximately 200 tons of lime was dropped into the Thames near the mouths of the sewers to try and take the smell away.

This solution wasn’t as effective as they would have liked and on the 15th of July, a bill was put to parliament to gain funds for addressing London’s sewers. The bill was passed in just 18 days and by the 2nd of August, it became law to provide more money to construct a massive new sewer scheme for London.

And so, Joseph William Bazalgette – the Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works, was hired to take charge of this new project.

The London Sewer Scheme

As predicted, the project was massive. The planning and preparation took its time, as did amassing the funds. Parliament initially offered £2.5 million, somewhere between £240 million and over a billion pounds in today’s values.

Bazalgette set to work preparing for the new system, reviewing 137 different proposals on how to handle the issue. The plan they settled on was for an extensive underground system of sewers that would join with the existing municipal drains. The system would funnel the waste far downstream out of the main city of London and eventually dumped into the Thames Estuary at high tide. The system dumped the sewage eight miles downstream, via pumping stations at Deptford and Abbey Mills.

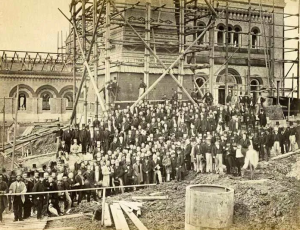

Crossness Pumping Station, Bazalgette Way, London, UK.

The plan involved building 1,100 miles of drains under London’s streets, to feed into 82 miles of new brick-lined sewers and carry the effluent to six “intercepting sewers”. Many of these had once been open streams, and “lost rivers” like the Fleet were brick-lined and covered over to become huge, hidden flows of waste.

There is no doubt that this project was massive. It required 318 million bricks, 670,000 cubic metres of concrete and thousands of labourers to dig out the tunnels. Demand for workers brought bricklayer wages up by 20%. Yet Bazalgette was still careful in his selections, using New Portland cement, which although new at the time, was known to be extremely strong and water-resistant, and is largely why the tunnels still stand today.

The Crossness Pumping Station during Construction

Understandably, the scale of the project meant it took time to settle on the plans and in 1859 the project commenced. Bazalgette also had to factor in the street runoff and two intercepting sewers were planned to run along the north and south banks of the Thames, to catch all the waste flowing downhill.

This presented the opportunity to build large new embankments along the river, encasing the sewer pipes and an underground tube line. New constructions narrowed the river, reclaiming about 22 acres of land from the Thames. The Victoria, Chelsea and Albert embankments were all designed by Bazalgette.

The system was officially opened in 1865 by Edward, the Prince of Wales, although the entire project was not completed until 1875. By the time of its completion, it could carry 2 billion litres of waste every day, enough to keep running even as the population of London exploded. The new sewage network’s enclosed design virtually eliminated cholera. Dr John Snow’s theory about cholera being a water-borne disease had been correct, although he died at the height of the Great Stink without knowing.

By the time Bazalgette died in 1891, 5.5 million people were living in inner London, over double the number when he first designed the sewers in the 1850s. However, Bazalgette’s forward-thinking ensured that the tunnels they constructed were double the size required to accommodate this growth. The brick-lined tunnels are still the basis of London’s sewer system today.