WATER HISTORY WEDNESDAY | EDITION 06

Most early civilisations were built around a constant and reliable source of water, usually in the form of rivers, with the Romans and the Tiber, the Egyptians and the Nile and the Indians near the Indus River. But in other areas, these were not viable options for water supply. So, what did they do for water?

The ancient Greeks are perhaps some of the most interesting with the way they avoided the establishment of major cities near rivers. This aversion to rivers was fed by a need for protection from floods as well as water-related diseases. It was such a strong belief that all major Greek cities since the Bronze Age, were established in areas under water scarcity.

The first towns of Greece were built on hills, which proved a challenge for water demands both due to the dry climate and the large distance from major bodies of water. As a result, the basic water supply and management elements included techniques to divert, retain and store flows. That’s where cisterns came in. The cistern was developed in early Greek civilisation in Minoa, Crete during the early Bronze Age and was refined throughout the ages. Cisterns were waterproof storage tanks often built underground or into the ground to collect runoff such as local rain and flood waters.

As expected, development in water technologies occurred when the available water supply was not meeting the needs of the settlement. For most, that meant looking at the transportation of surface water from rivers or streams when a population grew and the city expanded. In Greece, the advancements made were a result of the increasing need for a reliable water supply where surface water was not readily available, especially during periods of drought where rainwater couldn’t sustain the population. As a result, the Greeks were forced to consider groundwater exploitation.

Wells and water cisterns were the major water supply practices in prehistoric times before aqueduct technology was introduced. Rainwater collection in cisterns was first used for general domestic purposes, whereas groundwater was reserved for drinking water. Each city in Greece consisted of many cisterns and wells as their main means of water supply.

In the town of Palaikastro, several wells have been discovered, each usually ranging from 10 to 20m deep. These wells were hand-dug with bronze tools, with pots used to carry dirt away. The discovery of these well provides historians with important information about previous groundwater levels and the hydrogeology of the time with it providing clear indication that the Greeks were in a drought period.

During the Archaic period in Greece (known as the times that followed the Greek Dark Ages), evidence suggests a rise in the populations of Athens’ Agora between 1000 and 700 BC. Although Athens had at least 16 known wells at the time, this population increase proved to be demanding on their water supply, especially considering they were suffering from a drought at the time.

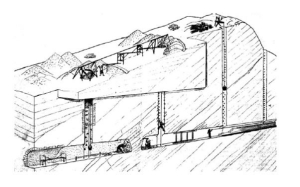

Technical details of the construction of the tunnels of the Peisistratid aqueduct.

This called for the construction of the first underground aqueduct, which was likely constructed during the tyrant Peisistratus around 560 to 527 BC. The conduit for the aqueduct (known as the Peisistratean aqueduct) was made of cylindrical terracotta pipes and was known to carry water to the Agora. A second aqueduct was constructed which carried groundwater from the hills of Hymettus (the mountain range in the Athens area of Attica, East Central Greece) to the centre of the city. This aqueduct spanned 7.5km from the Acropolis and consisted of tunnels and wells up to 14m deep.

This particular aqueduct worked like a qanat (meaning ‘chain of wells’), as previously touched on in the The Roman Aqueducts. Like any qanat, it consists of one underground tunnel and a sequence of shafts (known as the wells) that convey water by gravity to shallow aquifers in the highlands to the lowlands. The initial well of a qanat is constructed at the highest point of the mountain in order to find the groundwater level, with the shafts (wells) dug every 20-30m for the removal of soil and ventilation of the tunnel. The Hymettos aqueduct was a huge achievement for the Greeks and spoke to their own technological achievement, able to collect groundwater from alluvial fan deposits (fan-shaped deposits of water-transported material (alluvium)) and soft sedimentary rocks.

The philosophers, physicists and historians of the Archaic and Classical periods were extremely important in the growing understanding of the hydrological cycle and played a key role in the development of groundwater usage.

In the initial stages of the Greek’s use of wells, they had a basic understanding of how to find groundwater. At first, they could identify potential sources by considering the air of a location. They believed that if you could see mist rising from the surface of the earth it indicated water presence below. Other prospecting methods include the geological composition and the type of vegetation cover. According to the Roman physicist and historian Pliny, the morning mist that rose from the earth just before sunrise was the most reliable indicator of groundwater, as well as regarding the way the light reflected at a location at the hottest time of year and warmest time of the day.

Several Greek philosophers had developed correct explanations of the hydrologic cycle but it wasn’t until Anaxagoras of Athens and Empedocles of Agrigentum (c. 500-430 BC) that the cycle’s concept was clarified: the sun raises water from the sea into the atmosphere, from where it falls as rain and then it is collected as underground water. This theory was completed by Aristotle and Theophrastus (c. 384-287 BC) who clarified that water evaporates by the action of the sun and forms vapour whose condensation forms clouds, with the subsequent formation of surface water and groundwater.

This brings us much closer to the understanding of groundwater by the modern standard, with the Greeks’ knowledge further explored by the Romans to progress hydro-technology.